Today is the 19th August – our fifth “last day” on Qikiqtaruk. Weather rules over life in the Arctic, and especially travel. Any planning is to be taken with a generous shake of salt as sunshine quickly turns into rain, fog rolls in and strong winds blow across the island. Our scheduled departure was on the 15th August – a stormy day that made the landing of the Twin Otter plane that was to take us to Inuvik impossible. Since that first last day, we have been living in a strange mix of being in the moment and planning ahead, stuck in the limbo of Arctic unpredictability.

Now, five days later, I am sitting by the fire in Community House, once again awaiting news on whether or not our plane is coming. The sunshine days on Qikiqtaruk seem to be long gone, but today the weather is the best it has been in days. Dark, gloomy and rainy with the occasional snowflake, but still calm and relatively clear. Alas, that is not the situation in Inuvik, from where our plane is departing, and where fog has once again put a pause on our departure. It seems like today our departure is the most likely it’s been so far. My bags are packed, our field gear is put away in the warehouse, the floor is drying after our supposed final mop. These days of waiting, of not knowing whether or not we will leave, have given us extra time to take in the island, to wrap up extra field tasks, get crafty and reflect on our time here.

To check out Isla’s take on our final days on Qikiqtaruk in 2019, check out her blog post about what it’s like to be weathered in here.

15th August Thursday

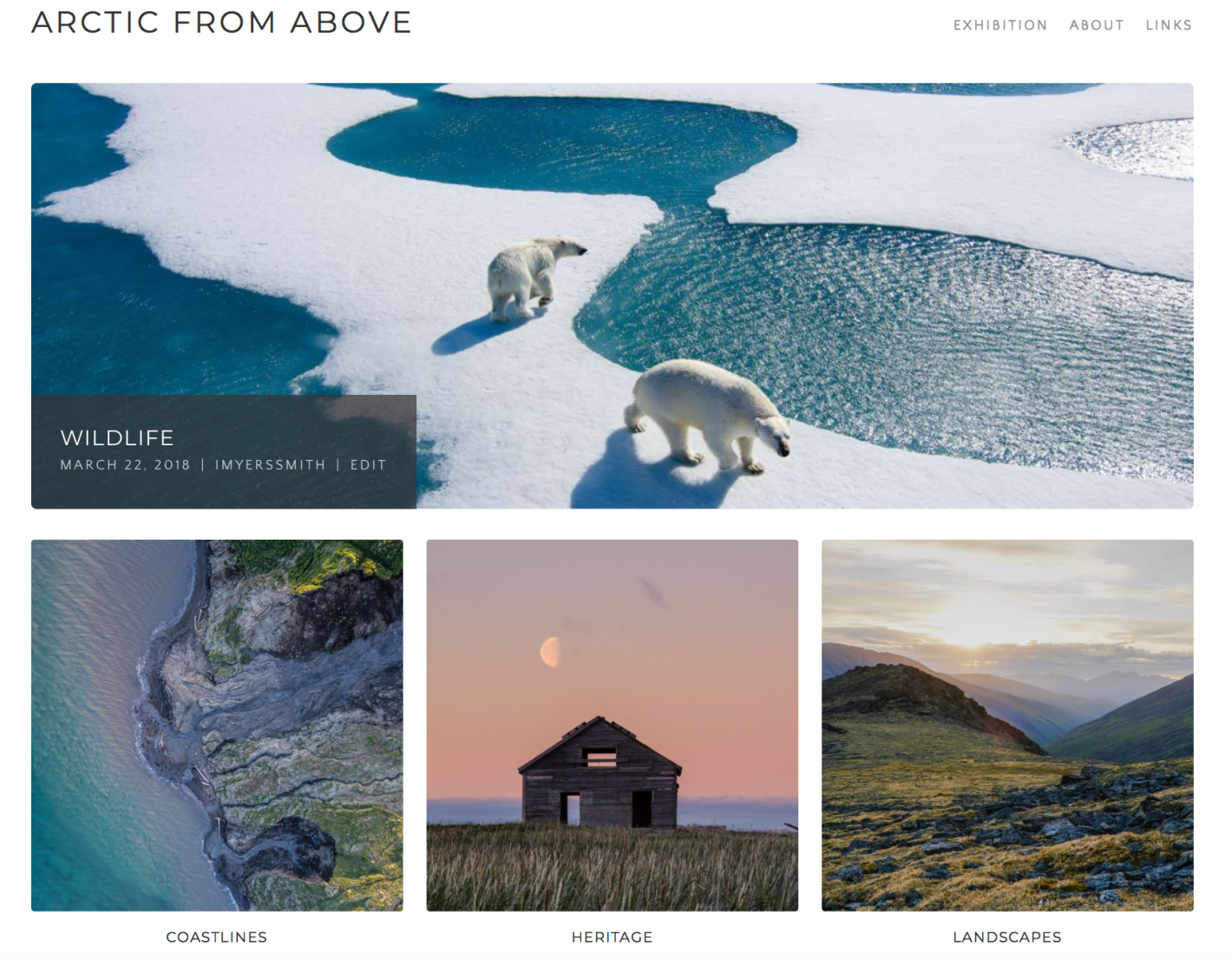

On our first last day, we woke up to a radio message from the rangers – “Polar bear, polar bear across the bay!”. We rushed outside in our pajamas to take a look at the polar bear in the distance. A young male, we thought, that walked up and down the hills and along the beach. As the bear approached a peregrine nest, the raptors went up in the air and angrily circled around the bear. Later on, a pair of gulls displayed the same behaviour. We watched the bear from a distance for a while and then hid away from the winds. We knew we are bound to be staying here for longer than we planned, but the exciting wildlife made up for any alterations in our plans.

16th August Friday

On our second last day, we knew that there were no available planes and thus we slept in and took our time finishing packing and tidying up. The smell of delicious cookies filled up the house and we each took to whatever activities we enjoy but often don’t find the time for during the more active part of the field season. As blank pages turned into paintings, wood took the shape of a bowhead and we signed our 2019 plaque, the day quickly progressed. Every once in a while, we would go outside to check the hills and see what the polar bear is up to. And on one of those checks, we saw a bear-looking animal but much darker than the polar bear we had been observing during the day. A large grizzly bear had come up on the horizon of the same hills where the polar bear was. The polar bear was lying among the tundra tussocks and eventually the grizzly walked away in the other direction without much action, but it was still exciting to see two different bear species at the same time.

17th August Saturday

On our third last day, we again took in the island, paused to reflect and adjusted to life in waiting. A big storm was once again raging across the island. The days were beginning to merge. We are not quite sure exactly what happened, but we do know that we did not see a polar bear.

18th August Sunday

On our fourth last day, we woke up early and after a look outside and no news of the plane, went back to bed. Painting, reading, word games with the youth from the Elders and Youth Program and wildlife sightings occupied most of our day. Winter felt particularly close that day, as the rain and wind chilled our bodies and made us run towards the fire after each venture outside. But for those that braved the outside world, a magical sight awaited. Four bowhead whales spent hours feeding close to shore in the cove – just where we usually run into the cold water after being in the sauna. That was the closest I have ever been to bowhead whales. I saw the bow-shaped markings giving them their name, their bodies curving as they rode the waves. We were all freezing, but the experience was more than worth it. Seeing the whales so up close and for quite a while as they went back and forth across the cove was a sight that resonated with everyone on the island. Whenever I turned my head away from the relentless wind, I saw people gazing at the whales and taking in the experience of being meters away from bowhead whales on a cold gloomy day in the Arctic.

19th August Monday

On our fifth last day, we woke up the earliest we have so far. Once again we packed and cleaned but there is still no sense of urgency in the air. Fog has descended across Inuvik and the plane is on standby. Time is both standing still, as we move back and forth from the kitchen to the fire and drink tea after tea, but it is also moving fast as each day of delay pushes our next destination and our lives beyond the island further into the future. We will continue waiting and at some point, thought it might not be today, we will rush to the airstrip, we will close our bags for real and leave Qikiqtaruk. It has been a summer wonderfully rich in discovery, wildlife encounters and emotions, and I am grateful for the chance to be here. As we have learned over the years, Qikiqtaruk can be a difficult place to leave, we have after all been trying for five days. But aside from the physical departure from the island, it is also hard for the experiences gathered here to leave my mind. And I know that in the months and years to come, I will often think back to my arctic summers.

Ten hours later, I am once again by the fire. As the day unfolded, we kept hearing about the fog at Shingle Point and that was the fog that ultimately pushed our flight once again. We filled our day with painting polar bears, writing letters and chatting with the rest of us here on the island. Moments ago, snow was falling from the skies in large snowflakes and the hills have quickly turned white. Though the snow is now almost all melted, the snowfall once again reminded us that summer is over and winter is quickly approaching. Though I’ve enjoyed many snowfalls around the world, this brief but intense snowfall on the island felt special. All my arctic experiences have been in the summer, and the white hills were a glimpse into what the island would look like after we are gone. It is now time to unzip my bags, take my sleeping bag out and settle in for another night on Qikiqtaruk.

20th August Tuesday

On our sixth last day on Qikiqtaruk, the snow returned early in the morning. The hills were completely blanketed by snow. The whole island shined brightly, the sun beams reflecting off the white surface. I went around Pauline Cove for a brief walk, but there was no haste in my steps. “We’re not going anywhere today.”, I had heard earlier. So having taken in the winter scenes, I went back to sleep. Three hours later, I emerged from my sleeping bag to make a cup of tea. Through the kitchen window, I saw someone pushing a wheel barrow full of boxes towards the airstrip. Could there be a plane coming after all? Stepping outside, the surrounding soundscape reminded me of spring. The sun was as blazing as it’s ever been this week and the sound of dripping water surrounded me. The snow was quickly disappearing and the familiar green tones of the tundra were coming back.

“The plane is leaving Inuvik!”, someone yelled from afar. It seemed unreal. It was day six of our prolonged departure from Qikiqtaruk and we were used to the plane not coming. And now it was on the way. The haste returned to our steps as we put away the cups from the tea we didn’t make and completed our final packing. With over five days of leaving preparations under our belt, we knew exactly what we need to do and very soon we were ready. A Twin Otter plane circled over the airstrip. And it landed. The first plane was for the people from the Elders and Youth program. It would fly back to Inuvik, refuel and then come back to pick us up on its second trip to Qikiqtaruk.

It was a beautiful and emotional final day on Qikiqtaruk. A day that goes to show how quickly things can change in the Arctic. The afternoon was so different from the morning. We bid goodbye to the rangers, the people we met over our time on the island, and to Qikiqtaruk. As we boarded the Twin Otter and Qikiqtaruk’s outline grew smaller and smaller in the distance, I knew that wherever I go next, I will always remember my Arctic summer.

Words, photos and videos by Gergana Daskalova

The “Isla Myers-Smith” bed – if you look closely you can see all the dead branches, but there are lots of new shoots as well.

The “Isla Myers-Smith” bed – if you look closely you can see all the dead branches, but there are lots of new shoots as well.